White arrows denote location of the Square within the photo.

Glynn county junior high, later known as Glynn Middle School.

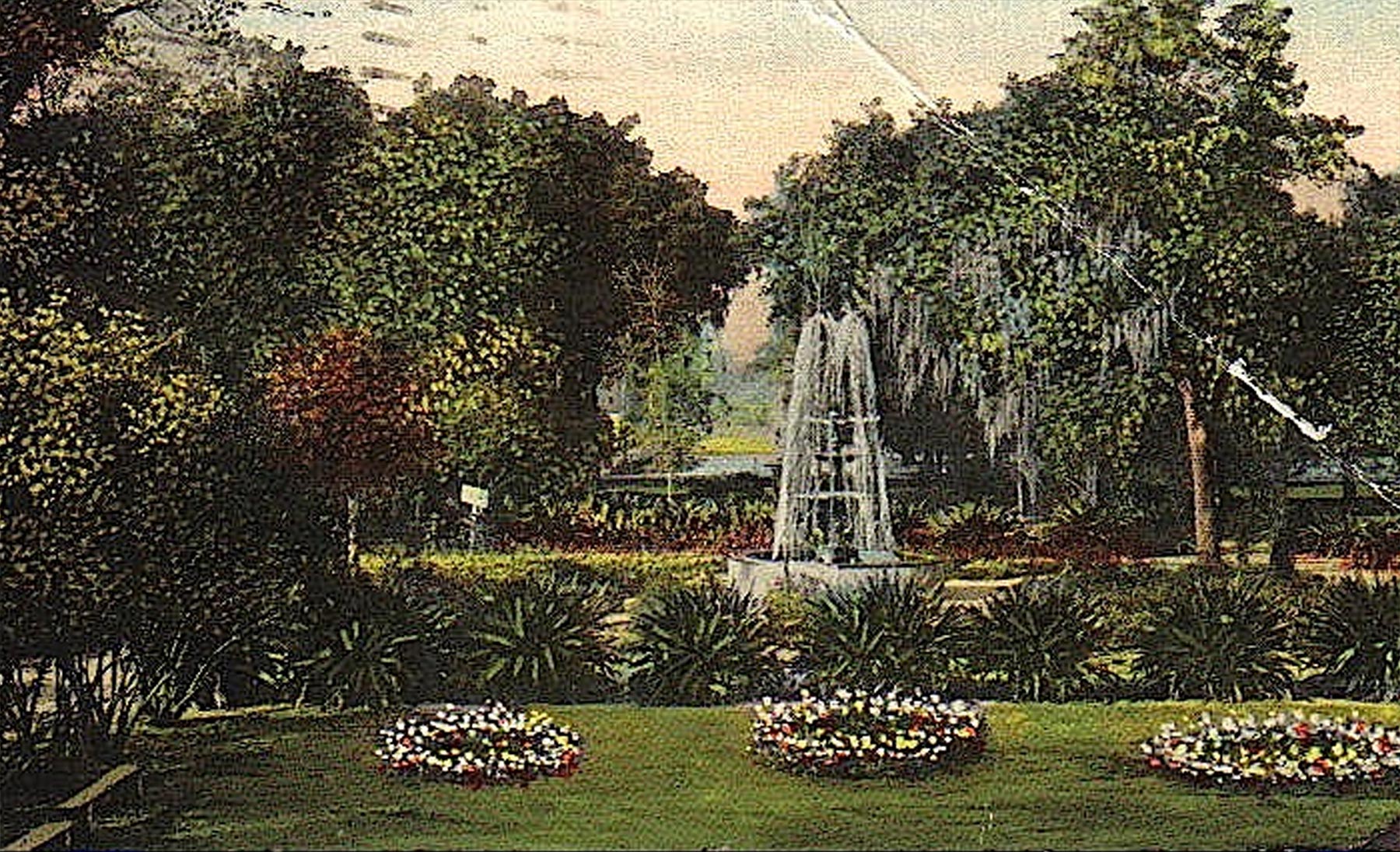

Wright Square, one of the two largest of the original 14 squares of Brunswick, was named after Georgia’s last Colonial Governor,

Sir James Wright

(1716-1785). Well-respected and fair, Wright held his office from October 13, 1760 until the end of the Revolution.

Georgia’s Wild Frontier

When Brunswick was established in 1771 near the southernmost boundary of the colony, the Provincial Council purchased a plantation owned by Captain Mark Carr, an officer in Oglethorpe’s Marine Boat Company, to locate the port city. Unlike earlier colonial towns, Brunswick had very little in the way of support and assistance from the Crown. Life was isolated and difficult, and the raw new city had virtually no amenities to offer immigrants from Europe.

Life for female settlers was extremely difficult and dangerous. Women were highly sought after for wives, but had very limited rights after they were married. Trustees of the Colony employed only one woman, a midwife, to encourage the establishment of families. After the Revolutionary War, that support was lost, and women faced the perils of childbirth in the wild new land without trained medical assistance.

Life in the New Nation

When settlers arrived in Brunswick, the colony was already in a state of unrest and on the brink of revolt. Brunswick’s Loyalist citizens abandoned the city during the Revolutionary War. When the war ended in 1781, the departing British left their Creek Indian allies with unpaid debts. As the new nation demanded more and more of their land, the displaced, angered Creeks repeatedly declared war on Georgia. Terrifying raids became an ever-present threat. Only a handful of families came back to the deserted town and started over again.

A Historic Discovery

For the first seventy years, the population of the city of Brunswick was concentrated within a few streets opened for use, mainly along what is now the downtown business corridor. Wright Square, and the streets approaching it, were merely lines on a map. The city’s first burial grounds were located within the square until the mid-1800s. As the city’s population grew and spread eastward, the exact location of the burial ground was lost. Since Brunswick’s early records were destroyed in a fire, no documentation was available to indicate the existence of a burial ground. Houses were built around the square, and no one had the slightest idea of what was beneath their tidy gardens and comfortable homes.

In 1952, Glynn County Middle School was built on the northern half of Wright Square. A modern middle school was built to replace it in a different location in 2009. In 2012, a land swap between the City of Brunswick and the Board of Education for the northern half of Wright Square was finalized. This provided the city the opportunity to re-connect the two halves of Wright Square back into a fully intact 4-acre historic square with the removal of George Street, which bisected the square when Glynn Middle School was built.

GLYNN COUNTY MIDDLE SCHOOL BUILT IN 1952 AND DEMOLISHED IN 2012. Courtesy Glynn County Board of Education.

THE OLD GLYNN MIDDLE SCHOOL BUILDING ON WRIGHT SQUARE DURING DEMOLITION.

Varying levels of skill for the difficult task of digging graves was evident, with some outlines displaying very irregular shapes while others had straight sides and square corners.

The graves appear to be arranged in family groups, with ample space between clusters of burial plots. The ages at the time of death, based on the size of the burial shaft, are approximate for those buried here. The relatively small number of graves for children under 6 years old suggests that there were probably few families in the rough frontier town. The angle of the coffin placements indicates the season of death, considering the Christian tradition of burial to face the rising sun, and the seasonal change of daily sunrise. Unlike early colonial settlements in New England, where the winters were harsh, the majority of deaths in Brunswick apparently occurred in summer months. Settlers from England were unaccustomed to the intense summer heat, and the origins of mosquito-borne diseases common in semi-tropical climates would remain unknown for more than a century.

EXPLORE THE GOOGLE STREET VIEW MAP.

No coffins were excavated or investigated, and no remains were disturbed. After the investigation was completed, the coffin shafts were respectfully covered again by the native soil. The identity of persons at repose in Wright Square remains a mystery. We may not know their names, but we honor them as the first citizens of our beautiful city.

Confrontations

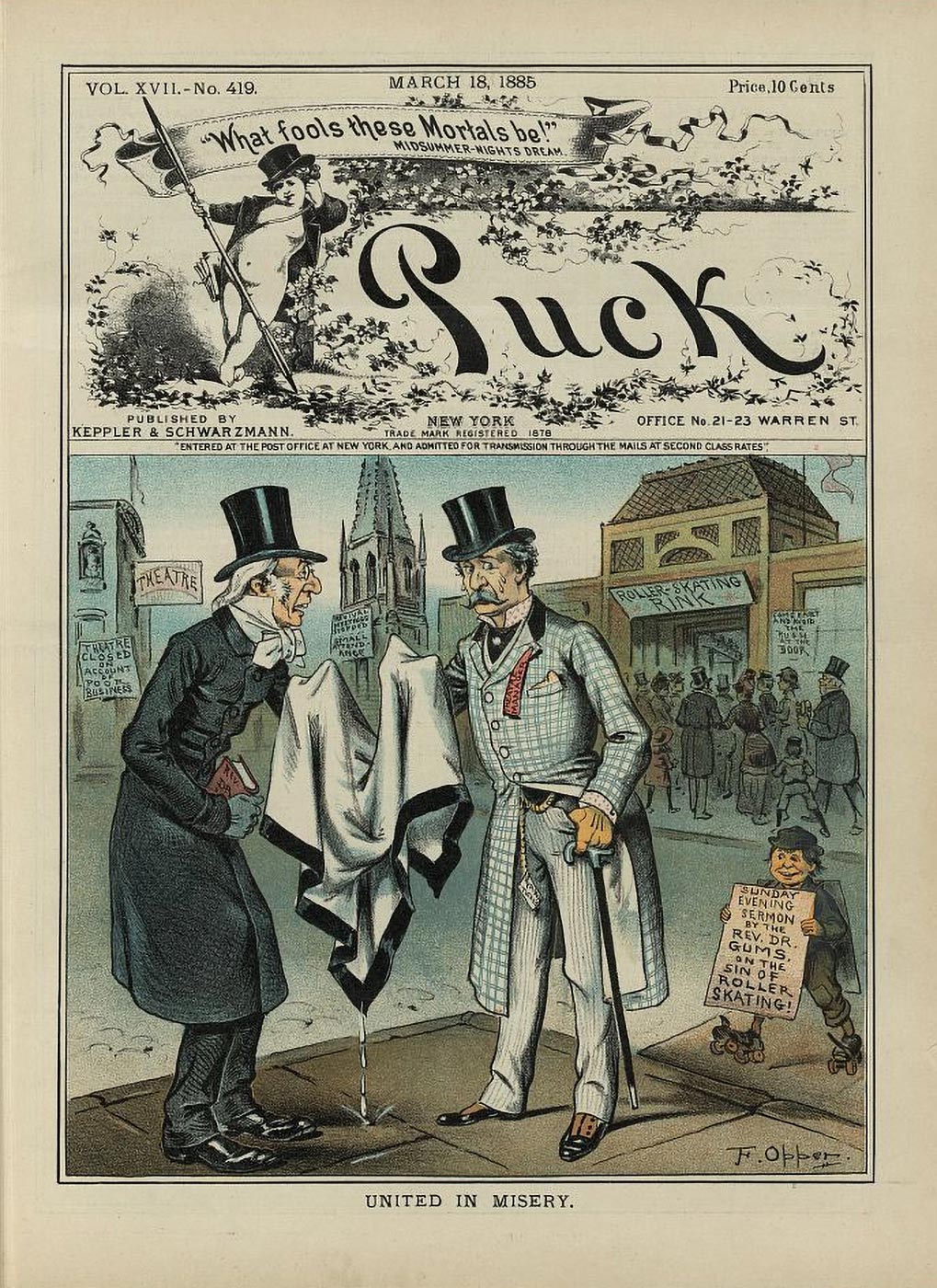

Over the past century, maintaining the original character and intention of Wright Square was challenged, as were many of the other original squares of Brunswick. The streets around Wright Square were first opened in 1859 at the request of the nearby Methodist Church to allow easier access to the church building as well as to the downtown business area. Thirty-five years later, the city allowed the installation of telegraph poles through the square. George Street was cut through the center of Wright Square soon afterwards, changing the configuration planned by the Royal Council in 1771.

Another challenge to the usual peace and quiet of the neighborhood around Wright Square came about in 1915, when the City Commission issued permits to have a skating rink built in the square. Roller skating was wildly popular, especially with young people. Skating rinks were viewed by elders with a suspicious eye. Seen as a sort of questionable teenage hangout, skating rinks were blamed by the press and from the pulpit for a number of modern shifts in proper behavior. Not only were the structures a cauldron of youthful, marginally supervised energy, but they were unbearably loud. Wooden floors with hundreds of metal wheels rolling over them would make a dreadful noise and certainly disrupt the quiet of a sedate residential neighborhood. An organized citizen protest reversed the decision to allow construction.

Plans are currently underway for a large restoration and beautification project in Wright Square scheduled to begin in 2021. The roadway around Wright Square will be modified to a one-way flow and George Street, which currently bisects the square, will be removed.